Хорошие немцы

Sep. 6th, 2022 06:01 pm

Борис Гребенщиков: «Позор Третьего рейха не бросает никакой тени на Баха, Бетховена и Гете.» https://novayagazeta.eu/articles/2022/09/03/skolko-mozhno-schitat-sebia-zhertvoi

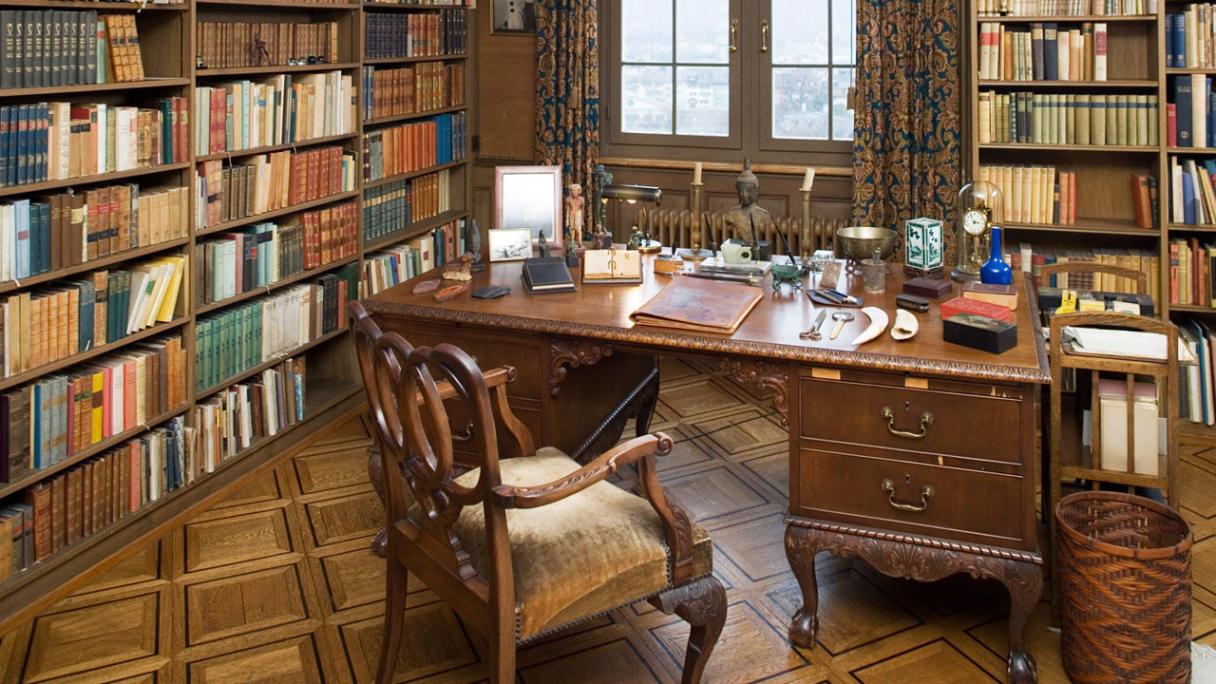

Весной 1941 прославленный немецкий писатель и Нобелевский лауреат Томас Манн переехал в Лос Анджелес из Принстона и приобрёл дом в Pacific Palicades. По соседству жили многие другие немецкие писатели и деятели культуры, бежавшие от Гитлера: Лион Фейхтвангер, Бертольд Брехт и т.д. Многие из них не планировали оставаться в Америке навсегда и мечтали о возвращении на родину, но, как и Стравинского и Рахманинова, Южная Калифорния привлекала их мягким климатом, близостью Голливуда и доступным по тем временам жильём. Заставленные книгами роскошные виллы Манна и Фейхтвангера быстро превратились в салоны, в которых бывшие соотечественники собирались на горячие дискуссии о культуре и текущих событиях.

You can visit all the addresses in the course of a long day. Bertolt Brecht lived in a two-story clapboard house on Twenty-sixth Street, in Santa Monica. The novelist Heinrich Mann resided a few blocks away, on Montana Avenue. The screenwriter Salka Viertel held gatherings on Mabery Road, near the Santa Monica beach. Alfred Döblin, the author of “Berlin Alexanderplatz,” had a place on Citrus Avenue, in Hollywood. His colleague Lion Feuchtwanger occupied the Villa Aurora, a Spanish-style mansion overlooking the Pacific; among its amusements was a Hitler dartboard. Vicki Baum, whose novel “Grand Hotel” brought her a screenwriting career, had a house on Amalfi Drive, near the leftist composer Hanns Eisler. Alma Mahler-Werfel, the widow of Gustav Mahler, lived with her third husband, the best-selling Austrian writer Franz Werfel, on North Bedford Drive, next door to the conductor Bruno Walter. Elisabeth Hauptmann, the co-author of “The Threepenny Opera,” lived in Mandeville Canyon, at the actor Peter Lorre’s ranch. The philosopher Theodor W. Adorno rented a duplex apartment on Kenter Avenue, meeting with Max Horkheimer, who lived nearby, to write the post-Marxist jeremiad “Dialectic of Enlightenment.” At a suitably lofty remove, on San Remo Drive, was Thomas Mann, Heinrich’s brother, the august author of “The Magic Mountain.”

In the nineteen-forties, the West Side of Los Angeles effectively became the capital of German literature in exile. It was as if the cafés of Berlin, Munich, and Vienna had disgorged their clientele onto Sunset Boulevard. The writers were at the core of a European émigré community that also included the film directors Fritz Lang, Max Ophuls, Otto Preminger, Jean Renoir, Robert Siodmak, Douglas Sirk, Billy Wilder, and William Wyler; the theatre directors Max Reinhardt and Leopold Jessner; the actors Marlene Dietrich and Hedy Lamarr; the architects Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra; and the composers Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Sergei Rachmaninoff. Seldom in human history has one city hosted such a staggering convocation of talent.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/03/09/the-haunted-california-idyll-of-german-writers-in-exile

Идиллия закончится через несколько лет после войны, когда немецкие иммигранты левых взглядов попадут под каток маккартизма. Бертольд Брехт уедет в Германию на следующий день после показаний по повестке в Конгрессе в октябре 1947. Американские оккупационные власти не пускают его в Мюнхен и он едет в Восточный Берлин, где будет обласкан коммунистической властью, которая тем не менее относится к нему с недоверием.

Brecht’s testimony has become somewhat legendary. The man who invented the theater of alienation turns this hearing into something of a piece of theater. Brecht did not lie to the committee; he denied official membership of any Communist Party, which was true. But his politics were decidedly problematic for HUAC. Instead of discussing them directly, Brecht gave answers that were often equivocal, ironic, or seemingly evasive, turning (like Bill Clinton’s post-Lewinsky testimony) on small matters of definition, or making use of the ambiguities of translation. For example, Chief Investigator Robert Stripling asks Brecht about a song entitled “Forward We’ve Not Forgotten” (from his play, The Decision) then reads an English translation of the song. Asked if he had written it, Brecht responds, “No, I wrote a German poem, but that is very different from this thing,” provoking laughter among the audience. In response to the question about his “revolutionary” writings, Brecht cleverly responds: “I have written a number of poems and songs and plays in the fight against Hitler, and of course they can be considered therefore as revolutionary, ‘cause I of course was for the overthrow of that government.”

https://www.openculture.com/2012/11/bertolt_brecht_testifies_before_the_house_un-american_activities_committee_1947.html

В СССР театр по методу Брехта, созданный Юрием Любимовым на Таганке, станет небольшой отдушиной для интеллигенции.

"Мы не рассчитывали на новое театральное дело, принимаясь в Вахтанговском училище за «Доброго человека из Сезуана», мы просто остановились на пьесе, которая давала возможность выразить те мысли по поводу жизни и — что очень важно — по поводу театра, которые меня и моих учеников волновали. Так получилось, что с «Доброго человека» начался наш театр.

Наши мысли о будущем тоже тесно связаны с Брехтом.

В этом драматурге нас привлекает абсолютная ясность мировоззрения. Мне ясно, что он любит, что ненавидит, и я горячо разделяю его отношение к жизни. И к театру, то есть меня увлекает эстетика Брехта. Есть театр Шекспира, театр Мольера, есть и театр Брехта — мы только прикоснулись к этому богатству.

Мне важно также, что Брехт, видимо, близок тому зрителю, которого я могу назвать дорогим мне зрителем. Самой лучшей, самой чуткой аудиторией, с которой мы встречались, были физики города Дубны. Я еще никогда не видел, чтобы зрители так реагировали на эстетические моменты спектакля. Брехтовский неожиданный поворот действия, построение мизансцены, острота внутреннего хода — на все была реакция точная и непосредственная. А когда эта аудитория принялась обсуждать наш спектакль, мы были поражены знаниями выступавших в области литературы и театра. Мы встретились с аудиторией, которая не меньше, а, может быть, больше нас знала искусство. То же самое повторилось в институте химии, которым руководит академик Семенов. Так что если мечты о театре захватывают проблему зрителя, то я мечтаю о таком зрителе."

https://fondlubimova.com/o-yurii-lyubimove/vremya-lyubimova/moskovskij-teatr-dramy-i-komedii-yurij-lyubimov-teatr-4-2-04-1965/

Владимир Высоцкий в любимой для него роли Галилея как бы напрямую обращался к "физикам города Дубны" со словами Брехта о моральной ответственности ученых:

"В свободные часы - у меня теперь их много - я размышлял над тем, что со мной произошло, и думал о том, как должен будет оценить это мир науки, к которому я сам себя уже не причисляю. Даже торговец шерстью должен заботиться не только о том, чтобы самому подешевле купить и подороже продать, но еще и о том, чтобы вообще могла вестись беспрепятственно торговля шерстью. Поэтому научная деятельность, как представляется мне, требует особого мужества.

Наука распространяет знания, добытые с помощью сомнений. Добывая знания обо всем и для всех, она стремится всех сделать сомневающимися. Но князья, помещики и духовенство погружают большинство населения в искрящийся туман - туман суеверий и старых слов, - туман, который скрывает темные делишки власть имущих. Нищета, в которой прозябает большинство, стара, как горы, и с высоты амвонов и кафедр ее объявляют такой же неразрушимой, как горы. Наше новое искусство сомнения восхитило множество людей. Они вырвали из наших рук телескоп и направили его на своих угнетателей. И эти корыстные насильники, жадно присваивавшие плоды научных трудов, внезапно ощутили холодный, испытующий взгляд науки, направленный на тысячелетнюю, но искусственную нищету. Оказалось, что ее можно устранить, если устранить угнетателей. Они осыпали нас угрозами и взятками, перед которыми не могут устоять слабые души. Но можем ли мы отступиться от большинства народа и все же оставаться учеными? <...>

Я был ученым, который имел беспримерные и неповторимые возможности, Ведь именно в мое время астрономия вышла на рыночные площади. При этих совершенно исключительных обстоятельствах стойкость одного человека могла бы вызвать большие потрясения. Если б я устоял, то ученые-естествоиспытатели могли бы выработать нечто вроде Гиппократовой присяги врачей - торжественную клятву применять свои знания только на благо человечества! А в тех условиях, какие создались теперь, можно рассчитывать - в наилучшем случае - на породу изобретательных карликов, которых будут нанимать, чтобы они служили любым целям. И к тому же я убедился, Сарти, что мне никогда не грозила настоящая опасность. В течение нескольких лет я был так же силен, как и власти. Но я отдал свои знания власть имущим, чтобы те их употребили, или не употребили, или злоупотребили ими - как им заблагорассудится - в их собственных интересах.

Я предал свое призвание. И человека, который совершает то, что совершил я, нельзя терпеть в рядах людей науки."

http://www.lib.ru/INPROZ/BREHT/breht2_5.txt

Во время войны идея "выработать нечто вроде Гиппократовой присяги врачей" была осуществлена пострадавшей от маккартизма Джин Уэлтфиш, выросшей в немецкоговорящей семье еврейских иммигрантов из Германии.

Маккартизм докатился и до другим иммигрантов. Лиону Фейхтвангеру отказали в американском гражданстве, и он боялся выехать из страны. Томас Манн, получивший гражданство в 1944, вынужденно в 77-летнем возрасте бежал в Европу в 1952, чтобы провести свои последние годы в Швейцарии.

В Швейцарии жил его друг Герман Гессе. Гессе был противником нацизма и помогал Манну, Брехту и другим выбраться из Германии после прихода Гитлера. Но Гессе избегал публично высказываться по политическим вопросам. Его книги были запрещены в нацистской Германии только в 1943, после выпуска аполитичной "Игра в бисер". В 1946 Нобелевская премия Гессе была призвана показать, что, невзирая на войну, немецкая литература остается в сокровищнице мировой культуры.

В 1937 Манн писал о Гессе (в переводе на английский): "There is nothing more German than this writer and his life's work - nothing that could be conceivably more German in the old, joyous, free and spiritual sense of the word, the one that has given the German name its best reputation and earned it the gratitude of mankind."

Преступления нацизма заставили пересмотреть отношение к немецкой культуре и истории. В мае 1945 Манн выступает в Библиотеке Конгресса в Вашингтоне с публичной лекцией "Германия и немцы" ("Germany and the germans"). В своем выступлении он принциально отказывается делить немцев на "хороших" и "плохих" и раскрывает, каким образом все они, включая его самого, несут долю ответственности за происшедшее.

Three weeks after the surrender of Nazi German, on May 29, 1945, Thomas Mann delivered a speech at the Library of Congress about his homeland Germany and the Germans. The speech was much anticipated, for to the American audience Thomas Mann embodied "the Good Germany" and there was a need to understand how Hitler's "Bad Germany" had come into being and was able to inflict so much damage on the world. Mann had originally written the essay in German - Deutschland und die Deutschen - and his daughter Erika translated it for the speech, which was delivered in English. <...>

In his speech, Mann is quick to dispel the notion that he is condemning "Bad Germany" from a vantage point of a morally superior "Good Germany". For the qualities that led Germany down the path to mass destruction are contained within himself as well.

https://www.dialoginternational.com/dialog_international/2020/12/thomas-manns-speech-germany-and-the-germans.html

Ниже я цитирую отрывки из лекции Манна по новому переводу, приведенному в приложении к книжке "Wilhelm Furtwängler: Art and the Politics of the Unpolitical" (биографии анти-Манна - дирижера Вильгельмa Фуртвенглерa, который остался в Германии и служил Гитлеру в качестве "хорошего немца", сохранявшего культуру для последующих покелений).

Манн начинает лекцию с определения своей новой идентичности:

"As everything stands today, my kind of Germanness is preserved most fittingly in a hospitable cosmopolitan environment, the multiracial and multinational universe that is America. <...> As an American I am a citizen of the world – as is by nature the German, in spite of the caution of the world which at the same time is part of him, of his timidity of the world, about which it is hard to say whether it is actually based on arrogance or inborn provincialism, of an inferiority complex within the society of nations. Probably both."

Он сразу же говорит о непродуктивности попытки записать себя в "хорошие немцы", чтобы с позиции морального превосходства судить о "плохих немцах":

"The gruesome destiny of Germany, the monstrous catastrophe to which its modern history has now led, compels our interest, even if this interest does not command our sympathy. To try to arouse sympathy, to defend and to excuse Germany would certainly not be a fitting intention for a native German today. To play the judge out of compliance towards the immeasurable hatred which his people has been able to arouse, to curse and damn his people and to commend himself as the ‘good Germany’ completely in contrast to the wicked one over there with which one has nothing at all to do, that doesn’t seem to me to be particularly becoming. One has to be concerned with German destiny and German guilt if one is born a German."

Далее Манн говорит об извечной проблеме немецкого комплекса провинциальности, который соседтсвует с немецким же космополитизмом и который немцы вроде него ощущали, в частности, при посещении Швейцарии:

"I think I am looking at this in the right way, I believe I have experienced it from my childhood onwards. A journey from the Reich across Lake Constance into Switzerland was a journey from the provincial into the world, – however strange it may seem that Switzerland, a narrow country in comparison to the broad and mighty German Reich and its huge cities, could be perceived as the ‘World’. It was, and is, however, its justification: Switzerland, neutral, multilingual, French-influenced, breathing in the air of the West, was indeed, despite her diminutive size, much more the ‘World’, the European stage, than the political colossus in the North, where the word ‘international’ had long since become an insult and an arrogant provincialism had spoiled the atmosphere and made it musty.

That was the modern – nationalistic form of the German alienation from the world, German unworldliness, a profound world-clumsiness, which in earlier times together with a type of petty-bourgeois universalism, a cosmopolitanism in a nightcap as one might say, had made up the image of the German soul. Something scurrilous and supernatural, something secretive and sinister, something quietly daemonic had always attached to this image, to this unworldly and provincial German cosmopolitanism."

Он вскрывает демоническую часть немецкой культуре, которая присутствует в ней с глубины веков и находит художественное выражение в фаустовской сделке с Дьяволом.

"Our greatest poem, Goethe’s Faust, has as its hero a man at the boundary of the Middle Ages and Humanism, a God-fearing man who out of presumptuous drive for knowledge gives himself to magic and the Devil. Where the pride of intellect joins with the spiritually obsolete and with ancient bonds, there is the Devil. And the Devil, Luther’s Devil, Faust’s Devil, I want to see as a very German figure, and the pact with him, signed and sealed, to gain for a while all the treasures and power of the world at the cost of his soul’s salvation, as something peculiarly close to the German nature. A solitary thinker and searcher, a theologian and philosopher in his cell, who, wishing to enjoy and rule the world, signs away his soul to the Devil, – is this not just the right moment to see Germany in this light, today, where Germany is literally being carried off by the Devil?"

Не оставляет Манн и Баха с Бетховеном, рассуждая о немецкой музыкальности, как проявлении демонической стороны.

"They have given the West – I will not say its most beautiful and socially most binding but its deepest and most meaningful music, and the West has not withheld its thanks and recognition for this. At the same time the West has detected, and today detects more strongly than ever, that such musicality of the soul costs dear in another sphere, – in the political sphere, that of human coexistence."

Он также отдает должное Мартину Лютеру за вклад в демократизацию европейского общества, но отмечает при этом, что сам Лютер не разделял идей политической свободы.

"By restoring the immediacy of man’s relationship to God, he promoted European democracy, since ‘every man his own priest’ is democracy. German idealistic philosophy, the refinement of psychology through pietistic searchings of conscience, finally the self-conquest of Christian morality by morality, by the strictest adherence to the truth – for that was the deed, or misdeed, of Nietzsche – all this comes from Luther. He was the champion of freedom, but in German style, for he understood nothing of freedom. I do not now mean the freedom of the Christian, but political freedom, freedom of the citizen. The latter not only left him cold, but its stirrings and pretensions were deeply repugnant to him."

В середине лекции Манн подходит к своему центральному тезису. Неспособность немцев воспринять западные идеи свободы, по его мнению, была связана с их неспособностью определить собственную национальную идентичность. Немцам не довелось испытать рождение собственной национальности в огне революции подобное тому, через которое прошли французы.

"The ‘nation’ was born in the French Revolution; it is a revolutionary and libertarian idea that includes the humanitarian, and in an internal, political sense it means freedom and in an external political sense, Europe. Everything advantageous in the French political spirit rests on this fortunate unity; everything constricting and depressing in German patriotic enthusiasm rests on this unity never having come about. It might be said that the idea of ‘nation’ itself, in its historical connection with that of freedom, is foreign to Germany. It might be regarded as erroneous to call the Germans a nation, whether they or others are doing the calling. It is a mistake to apply the word ‘nationalism’ to their passion for their Fatherland. It represents the misuse of a French idea and creates misunderstandings. The same name should not be applied to two different things. The German idea of freedom is ‘völkisch’ and anti-European; it is always very close to the barbaric, even if it doesn’t explode into open and declared barbarity, as in our day."

Манн снова обращается к Гете и его трагической привязанности к своему народу, отвергающему свободу:

"The painful isolation of this great man, who approved of all that is broad and great (the supernational, Germany in the world, world literature) cannot in the Germany of his time, excited as it was by patriotism and freedom, be sufficiently appreciated. The decisive and dominating ideas, on which everything turned for him, were culture and barbarism, – and it was his fate to belong to a people to whom the idea of freedom, because it is directed only outwards against Europe and against culture, became barbarism."

Провинциальный космополитизм, который был призван заменить немцам их национальную идентичность, обернулся в реальности наихудшей формой национализма.

"Sometimes, and not least when we look at German history, we have the impression that the world is not the sole creation of God but a co-operative enterprise with someone else. We would like to ascribe to God the gracious fact that good can come out of evil. That evil so often comes out of good is apparently the contribution of the other party. The Germans might well ask why their good turns out evil, why it becomes evil in their hands. Take their original universalism and cosmopolitanism, their inner lack of boundaries, which may be understood as a spiritual appurtenance of their old supranational empire, the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. This is a highly valuable, positive inclination which, however, was turned into evil through a type of dialectical inversion. The Germans allowed themselves to be seduced into basing their claim to European hegemony – indeed to world rule – on their innate cosmopolitanism; in this way their claim became its exact opposite, the most presumptuous and threatening nationalism and imperialism. In the process they themselves noticed that they had once again come too late to nationalism, that it had outlived its time. So they replaced it with something more modern: the slogan of race – which promptly led them to monstrous crimes and plunged them into deepest misfortune."

Манн вспоминает великого Бисмарка и рассуждает о неизбежности вырождения созданного им Второго Рейха.

"Essentially Bismarck’s Reich had nothing to do with democracy or anything to do with nation in the democratic sense of the word. It was a pure power construct aiming towards European hegemony and, regardless of all modernity and sober efficiency, the empire of 1871 associated itself with memories of medieval glory and the age of the Saxon and Swabian rulers. What was both characteristic and threatening in this was the mixture of robust timeliness, efficient modernity and nostalgia, i.e. a highly technological form of Romanticism. Having come into existence through wars the Unholy German Empire of the Prussian nation could only be an empire of war. As such it has lived, a thorn in the flesh of the world, and as such it is now destroyed."

Прославленный немецкий романтизм оказался отравлен культом смерти.

"Goethe gave the laconic definition of the Classical as healthy and the Romantic as diseased; a painful formulation for anyone who loves the Romantic with all its sins and vices. But it is not to be denied that in its fairest, most ethereal but at the same time popular and sublime manifestations it carries within itself the seed of disease, like the rose bears the worm; its innermost nature is seduction, and what is more, seduction to death. This is its confusing paradox: while it revolutionarily advocates irrational life forces against abstract reason and shallow humanity, it possesses a deep affinity with death precisely through its devotion to the irrational and the past. In Germany, its real homeland, it has most strongly retained this iridescent ambiguity, as the glorification of the vital against the merely moral and at the same time as affinity with death. <...>

And, reduced to the miserable level of the masses, the level of Hitler, German Romanticism broke out into hysterical barbarism, in an intoxication and convulsion of arrogance and crime, which is now finding its hideous end in national catastrophe, in an unparalleled physical and psychical collapse."

Под конец Манн возвращается к невозможности деления Германии на "хорошую" и "плохую".

"This story should convince us of one thing: that there are not two Germanys, an evil and a good, but only one, the best of which turned out as evil through devilish cunning. The evil Germany is the good Germany gone astray, the good one in misfortune, in guilt and in ruin. It is therefore impossible for a German-born spirit simply to deny completely the evil, guilt-laden Germany and to declare: ‘I am the good, the noble and the just Germany in my white garment; I leave it to you to eradicate the evil one.’ Nothing that I have tried to say or fleetingly to indicate to you about Germany has come out of alien, cold or detached knowledge; it is all within me, I have experienced it all in my own person."

Он вспоминает, что германофобия - тоже немецкая традиция и что великий Гете предлагал развеять немцев по миру и во благо всего челевочества превратить их в диаспору.

"Nothing that a Frenchman, an Englishman or even an American has thrown in the face of his people can be compared to the stark home truths which great Germans such as Hölderlin, Goethe or Nietzsche have levelled against Germany. In conversation, at least, Goethe went so far as to wish for a German Diaspora. ‘Like the Jews’, he said, ‘the Germans must be transplanted and scattered over the world!’ And he added, ‘In order to develop the mass of good that lies in them, fully and to the benefit of the nations.’"

Лекция заканчивается на оптимистической ноте. Быть может, победа над нацизмом поможет наконец мятущемуся в поисках любви немецкому духу найти успокоение.

"It could indeed be that the liquidation of Nazism has opened the way to social reform in the world that offers the greatest possibilities of happiness for Germany’s innermost inclinations and needs. World economy, the reduced importance of political boundaries, a certain depoliticising of the state, the awakening of humanity to awareness of its practical unity, its first contemplation of a world state – how can all this social humanism which transcends bourgeois democracy, the humanism which is the object of great contention, be alien and repugnant to the German character? In the seclusion of the German there was always so much longing for the world in the solitude that made him evil is the wish, as we all know, to love and be loved."