Надежда и вера

Jul. 22nd, 2020 06:04 pm

Сегодняшняя историческая экскурсия - март 1988. Время неудач и реваншей, надежды и веры.

12 марта 1988 журнал «Огонёк» публикует (в сокращении) статью Карла Сагана «Наш общий враг». Статья наивная и оптимистичная. Саган пговорит о надежде на будущее и пытается взывать к здравому смыслу советских читателей.

Цитирую по оригиналу:

If no one else, alien or human, can extricate us from this deadly embrace, then there is only one remaining alternative: However painful it may be, we will just have to do it ourselves. A good start is to examine the historical facts as they might be viewed by the other side -- or by posterity, if any. Imagine first a Soviet observer considering some of the events of American history: The United States, founded on principles of freedom and liberty, was the last major nation to end chattel slavery; many of its founding fathers -- George Washington and Thomas Jefferson among them -- were slave owners; and racism was legally protected for a century after the slaves were freed. The United States has systematically violated more than 300 treaties it signed guaranteeing some of the rights of the original inhabitants of the country. In 1899, two years before becoming President, Theodore Roosevelt, in a widely admired speech, advocated "righteous war" as the sole means of achieving "national greatness." The United States invaded the Soviet Union in 1918 in an unsuccessful attempt to undo the Bolshevik Revolution. The United States invented nuclear weapons and was the first and only nation to explode them against civilian populations -- killing hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children in the process. The United States had operational plans for the nuclear annihilation of the Soviet Union before there even was a Soviet nuclear weapon, and it has been the chief innovator in the continuing nuclear arms race. The many recent contradictions between theory and practice in the United States include the present [Reagan] Administration, in high moral dudgeon, warning its allies not to sell arms to terrorist Iran while secretly doing just that; conducting worldwide covert wars in the name of democracy while opposing effective economic sanctions against a South African regime in which the vast majority of citizens have no political rights at all; being outraged at Iranian mining of the Persian Gulf as a violation of international law, while it has itself mined Nicaraguan harbors and subsequently fled from the jurisdiction of the World Court; vilifying Libya for killing children and in retaliation killing children; and denouncing the treatment of minorities in the Soviet Union, while America has more young black men in jail than in college. This is not just a matter of mean-spirited Soviet propaganda. Even people congenially disposed toward the United States may feel grave reservations about its real intentions, especially when Americans are reluctant to acknowledge the uncomfortable facts of their history.

Now imagine a Western observer considering some of the events in Soviet history. Marshal Tukhachevsky's marching orders on July 2, 1920, were, "On our bayonets we will bring peace and happiness to toiling humanity. Forward to the West!" Shortly after V.I. Lenin, in conversation with French delegates, remarked: "Yes, Soviet troops are in Warsaw. Soon Germany will be ours. We will reconquer Hungary. The Balkans will rise against capitalism. Italy will tremble. Bourgeois Europe is cracking at all its seams in this storm." Then contemplate the millions of Soviet citizens killed by Stalin's deliberate policy in the years between 1929 and World War II -- in forced collectivization, mass deportation of peasants, the resulting famine of 1932-33, and the great purges (in which almost the entire Communist Party hierarchy over the age of 35 was arrested and executed, and during which a new constitution that allegedly safeguarded the rights of Soviet citizens was proudly proclaimed). Then consider Stalin's decapitation of the Red Army, the secret protocol to his nonaggression pact with Hitler, and his refusal to believe in a Nazi invasion of the USSR even after it had begun -- and how many millions more were killed in consequence. Think of Soviet restrictions on civil liberties, freedom of expression, and the right to emigrate, and continuing endemic anti-Semitism and religious persecution. If, then, shortly after your nation is established, your highest military and civilian leaders boast about their intentions of invading neighboring states; if your absolute leader for almost half your history is someone who methodically killed millions of his own people; if, even now, your coins display your national symbol emblazoned over the whole world -- you can understand that citizens of other nations, even those with peaceful or credulous dispositions, may be skeptical of your present good intentions, however sincere and genuine they might be. This is not merely a matter of mean-spirited American propaganda. The problem is compounded if you pretend such things never happened. <...>

A central lesson of science is that to understand complex issues (or even simple ones), we must try to free our minds of dogma and to guarantee the freedom to publish, to contradict, and to experiment. Arguments from authority are unacceptable. We are all fallible, even leaders. But however clear it is that criticism is necessary for progress, governments tend to resist. The ultimate example is Hitler's Germany. Here is an excerpt from a speech by the Nazi Party leader Rudolf Hess on June 30, 1934: "One man remains beyond all criticism, and that is the Führer. This is because everyone senses and knows: He is always right, and he will always be right. The National Socialism of all of us in anchored in uncritical loyalty, in a surrender to the Führer."

The convenience of such a doctrine for national leaders is further clarified by Hitler's remark: "What good fortune for those in power that people do not think!" Widespread intellectual and moral docility may be convenient for leaders in the short term, but it is suicidal for nations in the long term. One of the criteria for national leadership should therefore be a talent for understanding, encouraging, and making constructive use of vigorous criticism.

So when those who once were silenced and humiliated by state terror now are able to speak out -- fledging civil libertarians flexing their wings -- of course they find it exhilarating, and so does any lover of freedom who witnesses it. Glasnost and perestroika exhibit to the rest of the world the human scope of the Soviet society that past policies have masked. They provide error-correcting mechanisms at all levels of Soviet society. They are essential for economic well-being. They permit real improvements in international cooperation and a major reversal of the nuclear arms race. Glasnost and perestroika are thus good for the Soviet Union and good for the United States. <...>

Although we must cooperate to an unprecedented degree, I am not arguing against healthy competition. But let us compete in finding ways to reverse the nuclear arms race and to make massive reductions in conventional forces; in eliminating government corruption; in making most of the world agriculturally self-sufficient. Let us vie in art and science, in music and literature, in technological innovation. Let us have a honesty race. Let us compete in relieving suffering and ignorance and disease; in respecting national independence worldwide; in formulating and implementing an ethic for responsible stewardship of the planet.

Let us learn from one another. Capitalism and socialism have been mutually borrowing methods and doctrine in largely unacknowledged plagiarisms for a century. Neither the US nor the Soviet Union has a monopoly on truth and virtue. I wold like to see us compete in cooperativeness. In the 1970s, apart from treaties constraining the nuclear arms race, we had some notable successes in working together -- the elimination of smallpox worldwide, efforts to prevent South African nuclear weapons development, the Apollo-Soyuz joint manned spaceflight. We can do much better. Let us begin with a few joint projects of great scope and vision -- in relief of starvation, especially in nations such as Ethiopia, which are victimized by superpower rivalry; in identifying and defusing long-term environmental catastrophes that are products of our technology; in fusion physics to provide a safe energy source for the future; in joint exploration of Mars, culminating in the first landing of human beings -- Soviets and Americans -- on another planet.

Perhaps we will destroy ourselves. Perhaps the common enemy within us will be too strong for us to recognize and overcome. Perhaps the world will be reduced to medieval conditions or far worse.

But I have hope. Lately there are signs of change -- tentative but in the right direction and, by previous standards of national behavior, swift. Is it possible that we -- we Americans, we Soviets, we humans -- are at last coming to our senses and beginning to work together on behalf of the species and the planet?

Nothing is promised. History has placed this burden on our shoulders. It is up to us to build a future worthy of our children and grandchildren.

http://alexpetrov.com/memes/hum/cmn_enemy.html

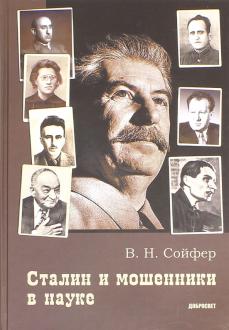

13 марта 1988 биофизик Валерий Сойфер с семьей лишен советского гражданства и выслан из СССР в США, где вскоре станет профессором и заведующим лабораторией молекулярной генетики в Университете Джорджа Мейсона.

До отъезда Сойферу удалось опубликовать в журнале "Огонек" статью об истории преследования генетики в СССР руками Сталина и Лысенко. Многие читатели впервые открывают для себя эту темную страницу истории.

За день до наступления 1988 года меня срочно пригласили в редакцию “Огонька”, где уже несколько месяцев лежала моя статья о Лысенко и Сталине. История с запрещением генетики в СССР была и остается одним из самых возмутительных проявлений политического диктата в сфере науки. Этот запрет повлек за собой отставание СССР на многих направлениях научных исследований — и не только в биологии, но и в медицине, сельском хозяйстве, ветеринарии и других областях. Статья была насыщена фактами и содержала ранее неизвестное письмо Лысенко Сталину, и когда я прочел эту статью друзьям, они в один голос заявили, что никто и никогда в Советском Союзе не решится ее опубликовать.

И вот неожиданно мне объяснили по телефону, что статья идет в ближайший номер. Я приехал в редакцию утром, а вышел из нее поздней ночью. При мне был набран в типографии текст, его прочитали еще раз редакторы, затем в течение пяти часов две дамы, знавшие, казалось, всё на свете и державшие в своих шкафах советские энциклопедии, справочники, решения съездов партии, проверили все до единой даты, цифры, имена и фамилии, встречавшиеся в статье. Иногда они звонили кому-то, и минут через двадцать из недр огромного здания издательства “Правда”, в котором располагается редакция “Огонька”, им приносили старые подшивки газет, давно изъятые из подавляющего большинства библиотек страны.

В тех случаях, когда я приводил факты, нигде не опубликованные, они требовали подтверждений, и я прямо из редакции много раз звонил старым московским генетикам, а также в Ленинград, Киев и другие города, связывая по телефону редакторов с оставшимися в живых людьми, которые подтверждали тот или иной факт и обещали прислать позже письменные подтверждения.

Я ушел из редакции за полночь, увидел на углу противоположного здания телефон-автомат и эзоповым языком объяснил жене, что всё в порядке. Я боялся, что подслушивавшие все наши разговоры гебешники могут что-то такое сделать и приостановить публикацию. Я всё еще не верил, что утром в киоски города поступит самый популярный в стране журнал с моей статьей, что впервые после почти десятилетнего перерыва на страницах советского издания появится мое имя, а на следующей неделе в этом же журнале будет напечатано продолжение статьи.

Хотя перед уходом я подписал последнюю корректуру, но меня интересовало: какие же купюры сделает цензура, если только она еще существует?

Первая часть статьи вышла без купюр. А вот во второй цензура показала свои когти. Через неделю я снова был вызван в редакцию, чтобы проверить все данные, приводимые в этой части статьи, и подписать корректуру. В самую последнюю минуту, когда секретарь Коротича уже подписала пропуск на выход из здания “Правды”, охраняемого милиционерами, и я направился по коридору к лифту, — я услышал разговор двух редакторов, двигавшихся по направлению к тому же лифту на полшага впереди меня. Одна из них задала другой вопрос: “А Сойферу об этом сказали?”. Они не знали меня в лицо и не думали, что автор может их услышать. Но я тут же догнал их, представился и спросил: “А о чем мне должны были сказать?”. Растерявшись, они сообщили, что цензура сняла из окончательного варианта все ссылки на газету “Правда”. Там, где я писал об информационных сообщениях и статьях в “Правде” и приводил соответствующие даты, номера выпусков и страницы, появились слова: “как сообщали газеты”, “в то утро в прессе все могли прочитать…”, “в письме, опубликованном в печати…” и т. д. Оказывается, горбачевские и яковлевские призывы к правде, к полной правде, к честному изложению истории не касались цензора, спрятанного в одном из бесчисленных кабинетов небоскреба издательства “Правда”. Для него ничего не изменилось, призывы к правде остались риторикой для дураков, а ошибки, допущенные газетой “Правда”, просто не существовали.

В ту минуту я не заметил еще одного факта произвола цензора. Вечером того дня, когда вышла вторая часть статьи, у меня дома собрались друзья — ученые и писатели (в их числе Ю.А. Карабчиевский). И вдруг один из гостей, Максим Франк-Каменецкий, закричал своим пронзительным голосом: “Боже мой! А где Сахаров? Они изъяли фамилию Сахарова!”. Я схватил журнал и увидел, что во фразе “Только благодаря принципиальной позиции академиков В А. Энгельгардта, И.Е. Тамма и А.Д. Сахарова Нуждин (подручный Лыненко, рвавшийся в академики. — B.C.) не прошел в академики…” — имя А.Д. Сахарова было заменено безликим словосочетанием — “и другие”. Кровь прилила мне к лицу. Я бросился звонить Андрею Дмитриевичу, чтобы сказать об этом произволе. Затем я заявил по телефону протест В. А. Коротичу, но уже по тону его понял, что он тут ни при чем. На следующее утро я принес в редакцию письменный протест против произвола цензора, мне обещали “при первой возможности” его опубликовать, но возможность эта так и не появилась. Меня начали усиленно выпихивать из СССР.

https://magazines.gorky.media/continent/1999/102/kompashka-ili-kak-menya-vyzhivali-iz-sssr.html

Безупречная репутация Сойфера поможет ему в 1990ые годы принять участие в Соросовской программе помощи российским ученым и учителям.

( Read more... )